Today Aizhan Abdubait is very famous in Kazakhstan. To date she has trained over 20 craftswomen. Her works are exhibited almost in all museums in our country; some of them are in private collections. She is an owner of a house of exclusive gold embroidery. We met her shortly before the opening of her personal exhibition in the city of Astana and discussed how she revived long-lost traditions of the delicate art.

In this regard southern Kazakhstan has always been a land of plenty. Aizhan’s great-grandfather was a jeweler, her grandmother sewed very well and during the Great Patriotic War she sewed clothes for the people from the small town of Chardara. That’s why Aizhan Abdubait believes that her skill is a gift of God and her lifelong work. Talent of .Aizhan’s ancestors helped her to become a master of extremely difficult and truly intellectual art — gold embroidery or "zerleu", "zer", as it is often referred to.

She grew in the atmosphere of creativity and decided to study traditions of needlework. Aizhan entered an art college and acquired an academic education there. However, during the college years she realised that applied art is not recognised by the Soviet society and considered to be a relic of the past.

Certainly, at that time people made attempts to revive their national applied art. Somebody put forward the idea to produce various objects in the national style for tourists. An industrial complex named "Kazkhudozhprom" was established for that purpose. At the same time, a factory "Tus kiiz" was opened. Nevertheless, none of these industrial facilities had the task to develop national applied art.

Being a member of the Union of Artists of the USSR Aizhan Abdubait created wonderful tapestries and trellises. Later she refused to continue this work and focused on Kazakh national art — she had been dreaming about it since her early childhood.

— Aizhan, please tell us how did you get interested in gold embroidery. At that moment the technique was lost and nobody was doing that in Kazakhstan.

— I studied works of Kazakh applied art and realised that every nation has its own concept of art and beauty. For example, Kazakhs didn’t have painting, easel graphics and sculpture as they were generally understood. However, our ancestors had applied arts, including processing of metals, leather and textile. By these means people expressed their perception of beauty.

Gold embroidery is a very ancient method of needlework in which women used gilded wire. It is very difficult now to find the origins of this technique. But, it is known that gold embroidery achieved its peak when the Ottoman Empire began expanding. At that time, this work is considered to be a palace art. Gold embroidery from Bukhara became known worldwide as it was recognised as the national interest.

At that period the art of zerleu was so appreciated that Kazakh language still contains some words related to it. For example, the word "zer" means both gold embroidery and intellect.

Unfortunately, very few objects of zerleu art have survived. Many products were brought from the country by the Geographic Society during the expeditions and foreigners who came here in the period of perestroika. It was a difficult chapter in the national history and to survive people had to sell old items.

— What were your first steps toward mastering the ancient art of gold embroidery?

— That was the most difficult moment. During my student years we had a good practice, once a week lecturers organised "museum day" for us. We visited a museum and examined the exhibits which we liked. Later we produced their copies. I do not know why but I always stopped in front of jacket of Khansha Fatima. And when I looked at it I knew how to embroider its elements. I was really surprised that somebody could not know how to do it or believe that embroidery had been glued to fabric.

Jacket of Khansha Fatima

I was attracted by gold embellished carpets from the museum of Abylkhan Kasteev. I never thought that I would be a master of gold embroidery. So, in fact, it’s the art that chose me. I just realised that I should do this.

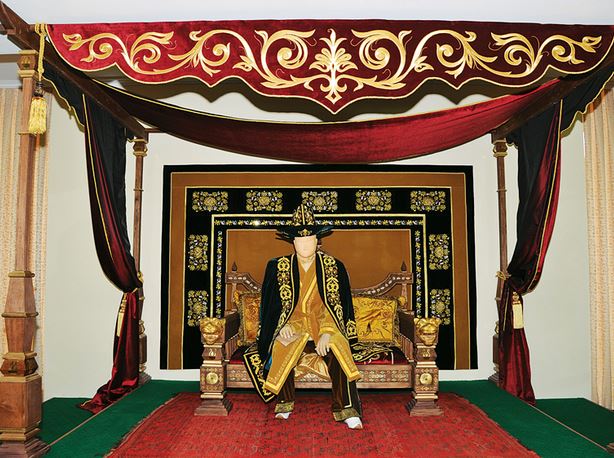

Khan’s residence, the city of Turkestan

In 1990 I designed a sketch of a chapan (caftan), but there was no gold thread in Kazakhstan. In 1994 for the first time I got it from India. In the years ahead, I started going there. I was the first who brought gold thread to Kazakhstan and worked with it. At that time I thought that it would be just a hobby. But it turned out that gold embroidery is a whole life and philosophy that required energy and patience.

— Do you improve your embroidery technique?

— Yes, of course. But, once again, it is almost impossible to reach the same level of excellence that existed in the past. We can say that we just have come closer to that level. I still am amazed that non-literate old women in the steppe could create such subjects.

— How traditional and specific are those patterns on gold embellished clothes?

— Today we do not know exactly what is Kazakh and what is not. It reflects negative consequences of the Soviet past when people avoided all national objects. It was the Soviet period when people started believing that "koshkar muyiz" ("mutton horns") is an original Kazakh pattern while others are non-Kazakh. Actually, it is a traditional floor pattern and people used it for decorating clothes.

My embroidery is based on patterns on antique items from our museums. All of them are decorated by plant ornaments. Uzbekali Zhanibekov and Alkey Margulan wrote that mostly Kazakh people used plant pattern for their clothes. And ornamental patterns were used for decorating household items.

— Aizhan, do you know how many works you produced using zerleu technique?

— I can’t answer this question, I have never counted. Once I tried to count those works that are kept in museums, but not all of my works are exhibited. My works include gold embellished carpets, copy of Khansha Fatima’s jacket (she was the second wife of Zhangirkhan), her dress which she wore for the coronation of Nicholas I, Ablaykhan’s chapan, uniform of Major General Zhangirkhan, and to name but e few.

Uniform of Major General Zhangirkhan, Khansha Fatima’s dress

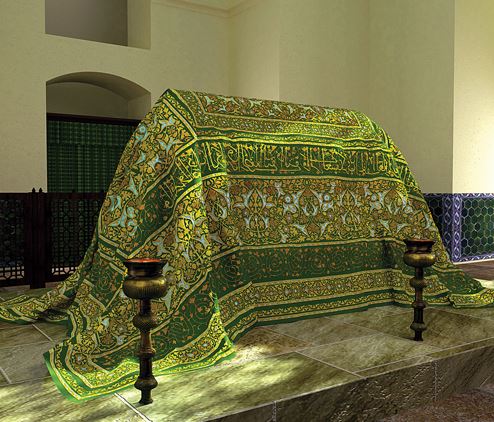

— I know that you have reconstructed tombstone cloth of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi. Please, tell about this work.

— I am proud of it and really happy that I had an opportunity to work on it. Today the reconstructed carpet is 4.5 metres by 6.5 metres in size (it was only 210 centimetres by 318 centimetres before). I started the work with searching a cloth. It took me eight month to do this! We found a yellow homespun cloth that looked like the original. We agreed to take it as I knew it would be easy to make it green. We requested Chinese and Turkish factories to help us but nobody could guarantee the necessary colour. Therefore, during two months we painted the cloth.

The history of the carpet is amazing. In 1946 a man brought it from Turkestan to the Central Museum of Carpets. There is a document showing evidence that the carpet "was sold for 28 roubles". Very long it was not exhibited being moth-eaten. Museum staff decided to write it off. Fortunately, there was a person interested in history and art — Uzbekali Zhanibekov. He got information about this carpet, took it from the museum and brought to Turkestan where asked to take care of it as it was a belonging of Ahmed Yasawi.

Nevertheless, it was still damaged. The tuft turned into rags, it chalked and people collected it to throw out. We were really sorry while reconstructing the carpet as we needed every piece of it. We were lucky because we had enough cloth to renew patterns. It can be claimed that the carpet was produced in the 16th century. And it hung in the mausoleum for at least 200-300 years.

Nowadays the reconstructed carpet is in the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi and original is kept in the Museum "Azret Sultan".

It is a very hard work to revive lost national embroidery technic but it is a good work. This is a tribute to beauty and traditions. Aizhan Abdubait produces unique artistic works based on the traditions of zerleu technique that was available only for a select few.

The personal exhibition of Aizhan Abdubait will remain in the Museum of the First President of Kazakhstan until March 2, 2015.

Lyudmila Vykhodchenko

Photos taken from vash-dom.kz and lifepvl.kz