Lyubov Ermolenko is a doctor of history, professor in the Department of Archaeology at the Kemerovo State University (Kemerovo, Russian Federation). She has been studying stone statues in Central Kazakhstan for more than 35 years. Today Lyubov Nikolaevna has told our web-site what the importance of these ancient monuments is and how can we preserve them for our descendants.

Lyubov Nikolaevna, you study stone statues in Central Kazakhstan. What got you interested in this sphere of archaeological investigation?

In my view, stone figures are one of the most exciting research topics. As a rule, an archaeologist deals with material remains of life of ancient communities, in particular with the world of objects created by people. Stone statues depicting human beings are not just products of ancient stone dressers. When you work with stone figures, it seems that you look in the mirror of history, where human faces of the past centuries are reflected. What they considered to be important? Why did they highlight some details of human image (for example, big eyes, or eyebrows scrunching together)? Why did ancient stone dressers depict the same poses (arm position), objects (such as vessel)? Each era in history had its own art. To understand it is a complicated and the most fascinating task. Furthermore, stone figures shouldn’t be studied independently of landscape characteristics, constructions, where they were placed, and so on. The statues-related research is a multi-faceted process.

Archaeologists find the same stone figures in other countries as well. What is the peculiarity of Kazakh balbals?

Let me start with the second part of the question. Very often journalists call stone figures "balbals". However, this is incorrect. Balbals are small stone poles which are placed in a row in front of a statue. According to the ancient runic inscriptions, balbals symbolized enemies killed by a hero. For instance, the inscription in honour of ruler of eastern Turks Bilge-Kagan contains the following: "after having killed their knights, I set balbals". Ancient Turkic statues, which depict warriors, are considered to be images of deceased (or fallen in a battle?) heroes.

Now, I answer the second part of the question. Stone figures of different ages were discovered in the territory of Kazakhstan. They trace back the period beginning from the late Bronze Age (the second and the first millennium BC) to the developed periods of the Middle Ages (at least, before the Mongolian invasion in the beginning of the 13th century). Some figures of the early Iron Age (the first millennium BC), more precisely Saka period, located in Central Kazakhstan, have a certain similarity with Scythian sculpture (steppes of the Black Sea coast and North Caucasus). Sanctuaries with unique statues of the second half of the first millennium BC were discovered in the territory of Mangistau and Ustyurt. These monuments are considered to be a heritage of Sarmatian tribes. Stone figures, which date back to the second half of the first millennium AD, are Turkic monuments. Turks were a powerful nomadic nation which established their own state (Kaganate) in Asian steppes. Later, it was broken up into the East-Turkic and West-Turkic Kaganates. Discovered in the territory of Kazakhstan statues were set by eastern Turks and slightly differ from those found in Mongolia, Tuva and Altai. Stone figures of the early second millennium AD in Kazakhstan were identified by scientists as monuments of Kypchak era. There are almost no such stones in areas to the east of Kazakhstan. At the same time, several tens of similar statues were discovered in the Northern Azov region (to the west of Kazakhstan). Kypchak groups, which migrated in the 11th century and then became known as Polovtsi (the Cuman), created them.

What are the differences between Turkic and Kypchak stone figures?

More generally, they differ in images and ways of installation.

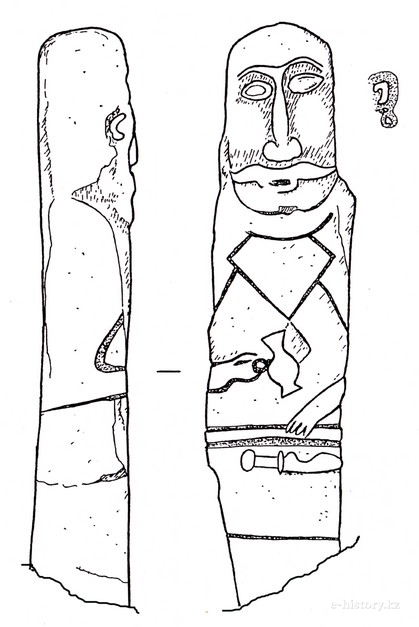

As a rule, ancient Turkic stones portray men, often with a vessel (goblet or bowl) in their right hand and blades on their belt. However, there are figures which depict human head only. Faces of most ancient Turkic statues express anger — bulging eyes, scrunching together eyebrows. Fury was an important fighting quality in those days, when firearm did not exist.

An ancient Turkic figure was put in the eastern side of quadrangular stone construction which is called "fence". A number of stone poles (balbals) could be installed to east from the figure.

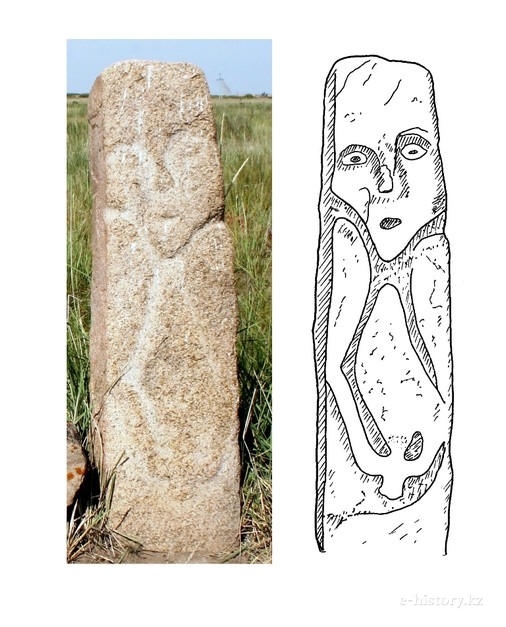

Ancient Turkic statue, placed near fence, faces east. It was found not far from the village of Sona in Aktogay area, Karaganda region.

A view of the statue, the rear side. Several balbals are put to east from the figure.

The figure found near the village of Sona.

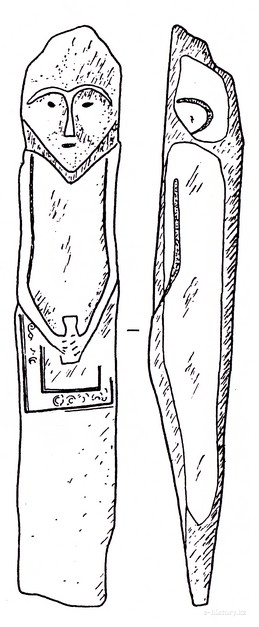

Kypchak statues depicted people with vessels in their both hands. Many scientists believe that they were ancestors of Kypchaks. If a vessel of ancient Turkic statues was at chest height, Kypchac figures hold it close to belly. Kypchac stone figures do not depict weapons or express anger. On the other hand, sometimes they highlight female and, less frequently, male signs. Some Kypchak statues reproduce human head.

Kypchak statues were placed at the east side or in the centre of a construction which resembled a burial mound. Such structures are commonly referred to as "Kypchak sanctuaries". A sanctuary could have one to five stone figures at the same time.

Kypchak sanctuary Zhaynakbay place. Aktogay area, Karaganda region.

Kypchak stone figure in Zhanaturmys mountain place. Shet area, Karaganda region.

In your opinion, why people made such monuments? What information their creators wanted to pass on?

Both ancient Turkic and Kypchak stone figures are considered to be memorial constructions, i. e. they were made in memory of those who had passed away. For example, ancient Turks believed that a stone is eternal, as evidenced by runic inscriptions. This means that production of stone statues was aimed at recording memory of heroes, ancestors. It is interesting to note that, unlike openly installed ancient Turkic figures, some Kypchak statues were hidden below mounds of sanctuaries, which looked like barrows. The ritual of hiding stone statues in such man-made "mountain" may have a link with a myth about the miraculous birth of ancestor inside a mountain. Probably, it is also connected with the belief that a deceased person, like the ancestor, should come back from the dead.

Very often the media report on thefts or deliberate destruction of stone figures. At the same time, it is obvious that statues suffer from adverse environmental conditions. What actions are taken by archaeologists in order to preserve them?

Unfortunately, stone figures are vulnerable. People destroy them by ignorance (having mixed figures up with stone blocks people use them in construction of walls of household outbuildings, and so on) or by malice. Time and natural disasters do not spare them (granite is vented out, crumble and peel off. The problem of preserving these unique monuments is of priority. Should we collect them in museums? But it seems that the stone figures, which were removed from ancient complexes and cast out of historical landscape, lose their unique peculiarity in museum expositions or near museum buildings. They looked like majestic monuments in Steppe. The primary role of archaeologists is to discover and study stone figures, ensuring their registration and protection. Another important task is promotion of scientific knowledge. A full understanding of cultural and historical value of statues will teach people to respect and protect these monuments.

You and Zholdasbek Kurmankulov have been involved in work of the expedition in Central Kazakhstan for nearly 20 years. I cannot fail to ask you about the most exciting moment of excavation for you.

Together with Zholdasbek Kurmankulov, Chief Researcher at the A. Kh. Margulan Institute of Archaeology, we have been studying stone statues from Saryarka for more than 35 years. We participate both in archaeological exploration and excavation.

Zh. Kurmankulov and L. Ermolenko at the site of the excavation. The Akshi Valley, Aktogay area, Karaganda region, 2009.

Participants of expedition do excavation work of a construction with stone figure of the Saka period. Aybas-Darasy mountain place, Ulutau area, Karaganda region, 2013.

L. Ermolenko at the site of the excavation of fence. Korgantas mountain place, Ulutau area, Karaganda region, 2011.

Turning to the memorable events, one of them was discovery of painted stone statue in Kypchak sanctuary at the Zhinishke River, Aktogay area, 1990. The upper parts of five figures protrude from the surface of barrow-shaped sanctuary before the work of expedition.

Kypchak sanctuary at the Zhinishke River before the excavation, 1990.

When the stone statues were just excavated from wet soil, Zholdasbek Kurmankulov succeeded in finding colours on one of them. He saw an "apron" which was drawn by yellow, red and black colours.

Coloured stone figure from the sanctuary at the Zhinishke River, Aktogay area, Karaganda region.

The Sun quickly dried the stone and the picture started disappearing in front of us. We rushed to make photos but something strange had happened: all devices, even film cameras, didn’t work. We had to work hard. To make photos and sketch the image archaeologists had to dampen the stone with water. The discovery of this stone figure was extremely significant. It proved that initially stone statues looked different; they were not colourless. It appeared that in the past stone figures could not only be coloured but also dressed in real clothes.

Inna Kuzmenko