The enterprise was nationalized after the October Revolution in the 1920s. How and when did it all start? Against the backdrop of what historical events occurred the development of the industry of the Akmola region?

During the scientific internship researcher, Ph.D. in Philology M.L. Anafinova had the opportunity to obtain a copy of the book "In the Kirgiz Steppes" by John W. Wardell in the library of Cambridge University, published in London by Gallery Press in 1961. To date, the Russian-Kazakh translation of the book "In the Kirgiz Steppes" is ready for publication. The book is richly illustrated with photographs and maps of Kazakhstan at that time; it describes not only everyday life and culture of the Kazakhs, the nature of the region, but the economic state and development of industry in Northern Kazakhstan. The dignity of the book is that the author managed to preserve in his documents the historicity, authenticity and, at the same time, his own vision of Northern Kazakhstan of that time. John W. Wardell is not a scholar-historian, not an ethnographer introduced the West his vision of the people of Kazakhstan, and their primordial ancient lands, the development of industry on this ancient land.

Madina Anafinova told us an amazing story of a British engineer who by some quirk of fate turned out to be in Kazakhstan. John W. Wardell served engineering training at the Office of Stockton Work, Wrightson and Company in the UK, where for three years he worked as a designer, specializing in ore development equipment, and in his spare time studying non-ferrous metallurgy.

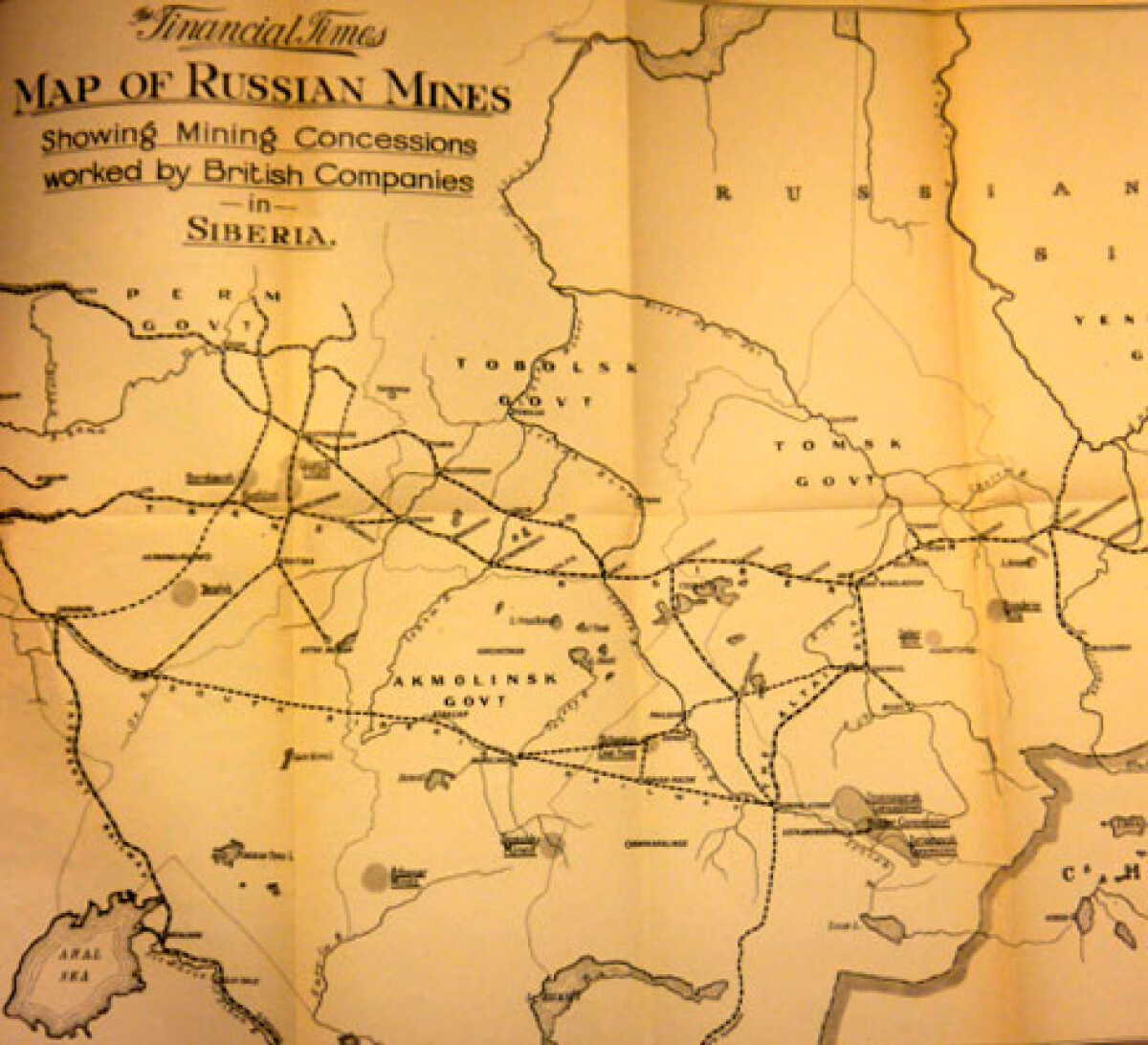

In November 1913, in order to improve his knowledge on this topic, and hoping to gain practical experience, he went to work for Walter J. Perkins, a consultant in the metallurgical industry in London, who was engaged in the development of projects for the Company Spassk Ore Deposits of the British Company with large ore Concessions in Siberia. These projects included the modernization of copper smelters at the Spassk Plant, the installation of an extractive and processing plant in Sarysu and Spassk, and equipment for mining and smelting operations for new Atbasar deposits of the same company.

By the end of April 1914 all the machines for this project had been ordered, most of the drawings for the construction of brick and wooden buildings were completed. It was decided to send three engineers from Walter J. Perkins to the Spassk Company as soon as possible to prepare the final work in the mines to assist in the construction work. In 1914, John Wardell, as a design engineer in the British company, along with other British specialists arrived at the Atbasar Mines of Akmola Province, and then at the Spassk Plant. Two engineers were sent to Atbasar, and John Wardell was chosen to be sent to Spassk. All of them had to leave England on May 16, 1914 with a contract until 1917.

Once in the millstone of the October Revolution, and after a long journey, Wardell returned to England only at the end of November 1919, after five and a half years. In February 1920, John Wardell once again went to work for the Management of Wrightson and the Company. In connection with the development of ore processing equipment, for five years he worked for the Company as their representative in London, and then was transferred to work at Stockton on Tees. Here, for three years, John Wardell worked as an engineer and chief designer, and the next thirty years as general manager.

John W. Wardell wanted to write the book after his return to London, when the whole Western world prayed for the collapse of the Russian Revolution, but the fall of the USSR did not happen. John W. Wardell published the book only after forty years of the existence of the Soviet Union. The author notes: "Since I was one of the few Englishmen who last visited Kazakhstan (if at all, after all, anyone else has been there since the creation of the Soviet Union), and the living conditions have since changed forever, I think that it is desirable to keep this report for the residents of the country, for history, about how the Kazakhs lived for centuries until great changes. To this I added a description of the country, its climate, and other details, records of my impressions of those five full years of events about the life of the British community, isolated in this remote part of the world. The first is important for understanding the country in which my adventures have taken place, the second, I hope, reflects my own ideas."

So John W. Wardell describes the events of those years. The group of Spassk deposits in Kazakhstan, where I lived for almost five years, settled in two settlements in the old part of Akmolinsk. The new settlement, founded in 1916, was in the old part of Semipalatinsk, but now all four settlements are in a new part of Karaganda. The main settlement where the smelting work was done was located in the Spassk Mills owned by the British Company, which I will continue to refer to as Spassk, as was customary during my two-year stay. Spassk is located about 725 kilometers south of Omsk. The most accessible city on the Trans-Siberian Railway is Petropavlovsk, which is 820 kilometers to the north-north-west; and the old capital of the region - Akmolinsk, is located 300 kilometers from the Spassk deposits along the same road. The closest point on the border of Xinjiang is 730 kilometers to the southeast; Lake Balkhash is 400 kilometers to the south-south-east. Two other earlier developments are the coal mine in Karaganda, 42 kilometers from Spassk on the Petropavlovsk road, and the Uspensky copper mine, which is shortly called Uspensky, 110 kilometers south-southwest of Spassk. The new settlement and development work was in Sarysu, ten miles from the Uspensky Road to Spassk and was my home for the next three years. Here, in Spassk, I met seven young people. Two of them were Cornish H.K. Robson and H. Pella were assistants to the smelting furnaces; two New Zealander - assistant factory R.J. Morgan and geologist H. Farmer; Canadian prospector J. Stevenson; Secretary from London R. Barker and Danish clerk T. Ristoft. The staff in Spassk consisted of J.V. Bryant, CEO, and Cornwall Bachelor of middle age who lived in a large, well-equipped house. This house also served as a hotel for Russian officials visiting the Company. The head of the plant, an elderly Englishman named Turner, worked in Russia almost all his life and chief accountant E.T. Boyce, an Englishman of middle age - both were married and lived in smaller buildings. In the south, from west to east, along the front of the plain are conveniently located houses for employees, Turner, Bryant, Boise's house and offices. D.E. Harbottle, a superintendent of a coal mine originally from Lancashire, lived in Karaganda. He was married and had two children. There also lived his assistant J. Campbell, an old bachelor from Scotland. In Uspensky lived married superintendent of the farm Farmer and an elderly New Zealander. Three assistants: Cornish H. Quirk and two New Zealander F. Larsen and K. Farmer were single. Inspector R.A. Purvis - my compatriot from the north was married and had a child. Mrs. Purvis, H. Farmer and C. Farmer were the children of the director of the mine. Including me, the full staff consisted of eighteen people and only I was from Britain itself.

In the first year of my two-year stay in Spassk, I was busy completing technical works for the reconstruction of the plant, and closing down the plant in Sarysu. In this I was helped by two Russian engineer-draftsmen, Baldin and Pavlovich. In the second year, when equipment from Great Britain and Russia arrived for the reconstruction of Spassk, other assistants were sent me. Soon the translation of the fourth chapter of the book, kindly provided by the scientist M.L. Anafinova will be presented to the attention of readers. The chapter "Spassk Fields" describes in detail the events that took place in the Spassk Fields in one of the most dramatic periods of our history.

Translated by Raushan MAKHMETZHANOVA